The polyvagal theory gives us a neurobiological framework that connects the mind, body, and emotions, helping us understand our behavior, particularly as it relates to trauma. The polyvagal theory is an evolutionary theory that takes us on a journey through our history, helping us understand how we have evolved as a species to learn, heal, and survive. We have a beautiful system that is always looking out for us, creating and modifying our internal landscape so that we can meet the demands of life.

Once you understand the beauty of this system, you will look at yourself differently. You will see your emotions as messengers, as biological functions that help you navigate life and help you learn. Thus, allowing you to experience the full spectrum of what it means to be human.

So, if you sometimes feel overwhelmed, know you’re not alone. When you are burned out, stressed, or when past traumas continue to resurface, the polyvagal theory may give you a framework that helps you understand what is going on in your body. You are not broken or dysfunctional. What you experience is your biology, working as it should, protecting you from danger and helping you heal. You will come to appreciate and have compassion for all the parts that make you you, and to flow with your biology. You have a beautiful mind-body system that knows how to take care of you.

THE POLYVAGAL THEORY

The polyvagal theory (PVT) was first introduced by Dr. Stephen Porges in 1994. Since that time, it has been widely used to explain how our bodies express what we experience in life and manage the ups and downs of our lived experiences; be it stress, trauma, or the joys of life. Through the lens of the Polyvagal Theory we are better able to understand how we handle stress, the importance of connecting to others, and how our autonomic nervous system is the key player in how well we navigate life. Best of all, you will learn ways to support your body by connecting with this mind-body system.

The polyvagal theory is a relatively newer theory, yet widely accepted and growing in application to different disciplines. Here, we will focus on the application to stress and trauma.

The polyvagal theory is a relatively newer theory, yet widely accepted and growing in application to different disciplines. Here, we will focus on the application to stress and trauma.

POLYVAGAL – WHAT IT MEANS

Polyvagal means many (poly) and wandering (vagal); the wandering nerve. The vagus nerve is one of twelve cranial nerves. Each of the twelve cranial nerves directly connects to different organs in the body, creating a bidirectional communication system. The vagus nerve is a key component of the PVT as it is both the longest nerve in the body, and it connects and communicates to many of our vital organs. The ability to connect and communicate to so many organs allows the vagus nerve to immediately give a ‘call to action’ to the biological functions needed to perform at any given moment. The vagus nerve is proposed to have a key role in self-regulation, our response to fear, and our connection to others.

You can imagine the vagus nerve acting like a railway switch, directing the body to function on the track that meets the demands of the moment. For example, if you need to travel fast and efficiently, the engineer will put the train on a track that allows fast and efficient travel. If you need to travel slowly and leisurely, a second track. And if the train needs to stop for repair, a third track is available. The train engineer knows the tracks and when to pull the switch to allow the train to head in the direction that meets the needs of the situation. The vagus nerve works much the same, with each track being a different physiological state.

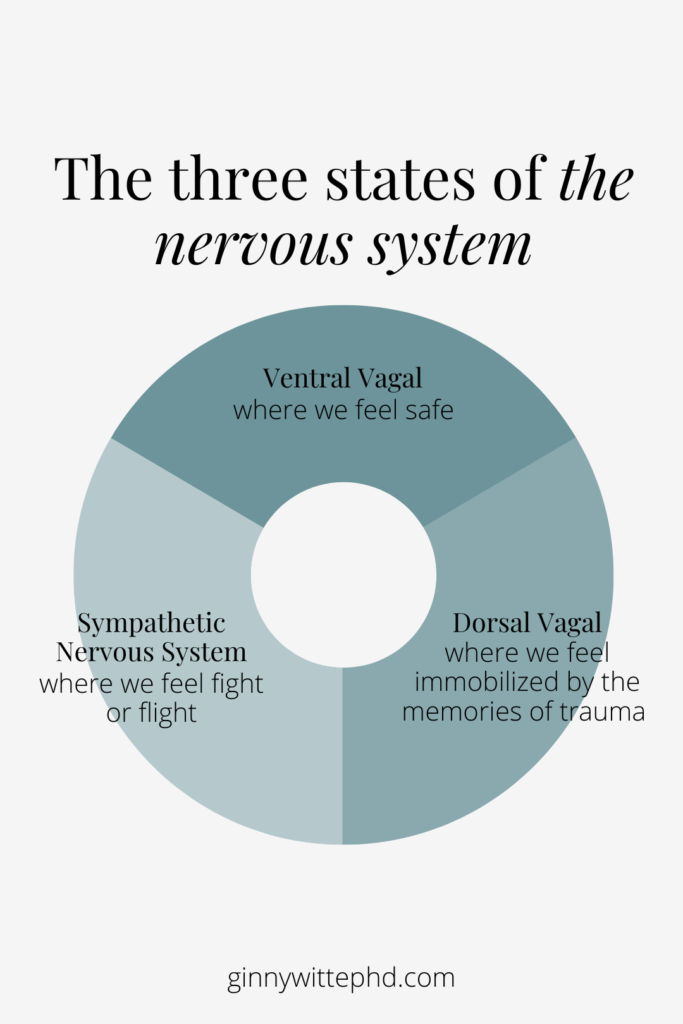

Each railway track metaphorically aligns with one of the the three basic physiological states of the nervous system. There are six; three basic states, two mixed states, and lastly a mixed state of appeasement. We will focus on the three basic states here.

Each railway track metaphorically aligns with one of the the three basic physiological states of the nervous system. There are six; three basic states, two mixed states, and lastly a mixed state of appeasement. We will focus on the three basic states here.

The Ventral Vagal State: Where We Feel Safe

Safety, joy, curiosity, connection, engagement . . . these words describe the ventral vagal state.

Imagine riding in the train on the slow and leisurely track. On this track you are relaxed. You enjoy a good book or a talk with a friend. You may take in the sights as you gaze out the window. You may have a friendly discourse on a topic with someone next to you. Or, you may savor a warm drink or meal as you travel. In this state life flows. We breathe deep, smile, and feel the goodness of life. We all love to be here. This is your ventral vagal state.

The ventral vagal state is the most recent development of the autonomic nervous system. As hunters and gatherers we could not survive independently, we needed to be part of a tribe. The ventral vagal system evolved to help us connect with our fellow humans. Our body language, our voice, smile, and eyes are wired to convey compassion, connection, and safety to one another. When we feel safe and connected, we work together, learn and solve problems.

This is also the state where the body connects to healing. It can rest from all the work it must do, allowing the organs to slow down, digest food, restore itself, and consolidate learning. You may know this as your ‘rest and digest’ state. Through connections to the heart, lungs, digestive and related organs the vagus nerve tells the organs all is well and they can focus on function and healing.

When we need to solve problems, we begin in this ventral vagal state. If we are not able to work together to solve problems through connection and cooperation, the body feels threatened. We’ve all felt this tension begin to rise when things don’t go well. It’s time to switch tracks. We need more support to manage this ‘felt sense’ of threat, so the body begins to mobilize.

When we need to solve problems, we begin in this ventral vagal state. If we are not able to work together to solve problems through connection and cooperation, the body feels threatened. We’ve all felt this tension begin to rise when things don’t go well. It’s time to switch tracks. We need more support to manage this ‘felt sense’ of threat, so the body begins to mobilize.

The Sympathetic Nervous System: the Need to Fight or Flee

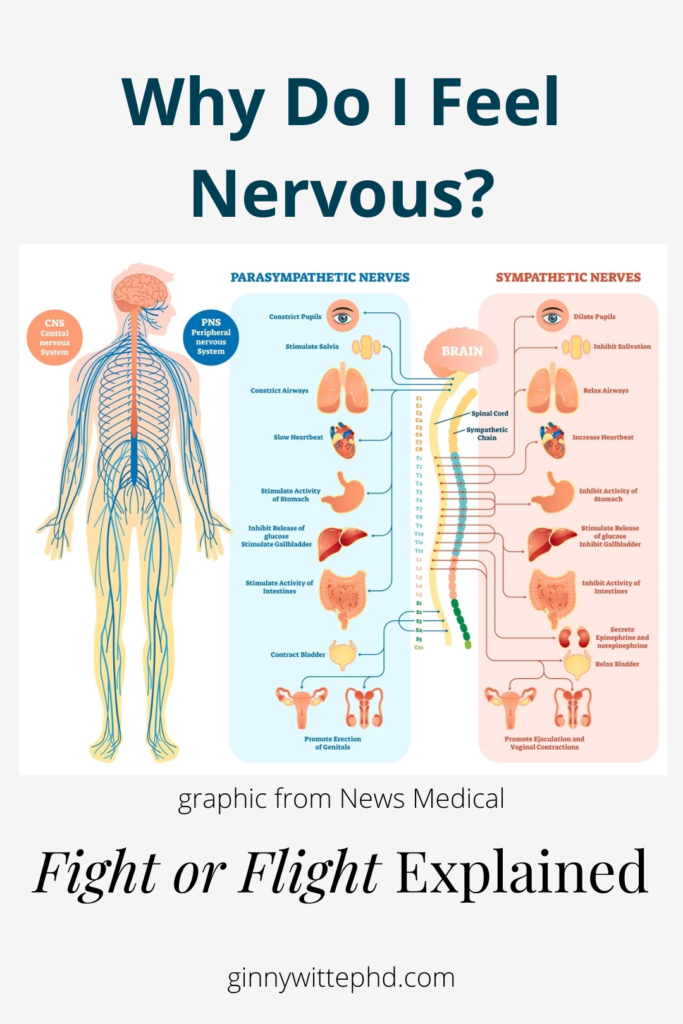

As we switch tracks, the body changes. You may feel anxiety, a pounding heart, a tight gut, sweaty palms, increased energy. These words describe the sympathetic nervous system state. Here your body prepares you for action, to protect your space, and to fight or flee if needed.

When you feel threatened, the hypothalamus sends a message to the autonomic nervous system to mobilize you to run or fight. You may recognize this as your fight/flight system. You may run or fight physically, or verbally, through verbal attacks and arguing. You may also run away into work, shopping, gambling, or other busy, distracting activities.

Body changes are noticeable as your adrenal glands pump out adrenaline, creating a cascade of physiological changes to prepare you to protect your space. Your heart rate and your blood pressure increase. The airways in your lungs open to increase your breathing capacity. Glucose is increased in your bloodstream to supply your body with increased energy. And your senses such as sight and sound become stronger to help you identify potential danger. You feel strong and powerful. A little of this energy is invigorating. Too much and we may panic, as the feelings seem to spill out like a bucket too full of water, being carried over uneven ground, sloshing everywhere.

Your autonomic nervous system is composed of two branches; a sympathetic branch and a parasympathetic branch. The ventral vagal state lives in the parasympathetic branch, while the flight / flight state lives in the sympathetic branch. The ventral vagal can be thought of as the brake, slowing you down, and the sympathetic branch as the gas pedal, pushing your energy output up.

It takes a great deal of our metabolic resources to be in a state of fighting or fleeing. These resources need to be replenished. Our stress response is meant for short-term stress, not long-term, or chronic stress. When we are in a chronic state of stress health problems occur and our body may eventually shut down to preserve valuable resources, including survival.

It takes a great deal of our metabolic resources to be in a state of fighting or fleeing. These resources need to be replenished. Our stress response is meant for short-term stress, not long-term, or chronic stress. When we are in a chronic state of stress health problems occur and our body may eventually shut down to preserve valuable resources, including survival.

When we can’t escape the threat through fighting or fleeing, we shut down. This may happen in a rape situation or a terrible accident where you are pinned down and cannot move.

Some see this as a ‘social death.’ Life is literally unbearable.

The Parasympathetic Nervous System: Dorsal Vagal

In the dorsal vagal state you have switched tracks again. Your nervous system has moved from fast to slow, back to the parasympathetic branch. But this time the branch goes south to the organs below the diaphragm.

A place of deep rest, restoration, and holding, or holding on . . . . you may feel spacy, numb, dissociated from your body, disconnected from others. Sometimes, you don’t feel, it’s too painful.

Here, your nervous system has down-shifted. In the sympathetic state you may have felt you couldn’t be still. In the dorsal state, you can’t move. This is not a conscious choice, it is the biology of your nervous system. It is your biology responding to a severe threat. In situations of PTSD, the threat is from the past, yet a reminder has surfaced and your body remembers the overwhelming experience, and reacts to protect you. Your biology thinks you are dealing with the trauma again, in the moment.

Here, your nervous system has down-shifted. In the sympathetic state you may have felt you couldn’t be still. In the dorsal state, you can’t move. This is not a conscious choice, it is the biology of your nervous system. It is your biology responding to a severe threat. In situations of PTSD, the threat is from the past, yet a reminder has surfaced and your body remembers the overwhelming experience, and reacts to protect you. Your biology thinks you are dealing with the trauma again, in the moment.

Coming out of the dorsal state is a slow process. You simply cannot rush it. You have to respect the body and listen to what it needs. Patience, kindness, and support are the necessary ingredients here.

Coming out of the dorsal state is a slow process. You simply cannot rush it. You have to respect the body and listen to what it needs. Patience, kindness, and support are the necessary ingredients here.

To move out of this dorsal state you must first move slowly and carefully back into the sympathetic state, and then into your ventral vagal state. This should be done with a trained therapist with somatic training to be able to move the body through the different states of your nervous system. In the dorsal state, life can seem so hopeless that you are not likely to self-heal.

*all photos are licensed by Canva

COMPASSION FOR SELF

Understanding these physiological states will allow you to have compassion for yourself and the biological process designed to serve you, not harm you. You will begin to notice when you are moving through these different states and engage in practices that return you to your ventral vagal state. You will switch tracks back and forth as you need to stay balanced. This we call self-regulation. We are not born self-regulating, we must practice and learn this skill.

We want to realize that there is a time and a purpose for each of these states. Allow yourself the time you need to nurture and care for your body, just as you would if you had an illness, or a physical wound. Be gentle with yourself. Your very first resource may be another gentle, loving soul with a smile that warms your heart, and a voice that soothes you. It may be a pet dog who snuggles next to your side, or on your lap. Or, it may be a rest in nature. The goal is to know your body and to find your path.

Overall, we want to have a flexible nervous system; one that can move between states fluidly as needed. Our days are filled with experiences that require us to be activated: such as a competition, performance, or giving a presentation. We also have moments where we need to quiet and calm ourselves: such as after a long day at work, or to transition to sleep. With practice and self-care you can avoid the extremes of each physiological state and adjust when needed. It may feel much like adjusting the volume up or down on a radio dial. We also help others to calm down or get excited. We call this coregulation.

Here we have the three basic states of your nervous system: the ventral vagal, the sympathetic, and the dorsal vagal. See if you can recognize them as you go through your day. Try and notice the activities or experiences that bring you in or out of each physiological state.

Here we have the three basic states of your nervous system: the ventral vagal, the sympathetic, and the dorsal vagal. See if you can recognize them as you go through your day. Try and notice the activities or experiences that bring you in or out of each physiological state.

I will share three mixed states with you in a future blog. These are states of play, of intimacy, and of pleasing and appeasing. Stay tuned . . . .

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Co.

Porges, S. W. (2009). The polyvagal theory: New insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 76,(Suppl 2): S86-S90. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76s2.1

Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116-143.